A couple of years ago a friend asked me: Why do you keep making all these art pilgrimages? It’s an interesting (and befuddling) experience being a person. We spend life looking outward through small and tricky orifices. We probably see ourselves the least clearly of all things. I didn’t know I made art pilgrimages. I’m still thinking about that question. But the fact someone thought I did became the final inspiration to begin blogging on the subject.

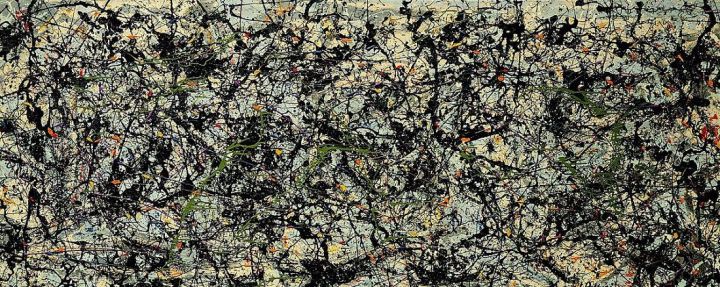

When we visited the new Anderson Collection at Stanford University a few weeks ago, my husband, Jim, bought the collection catalog, A Family Affair, as my birthday gift. Last week I wrote about the experience of viewing Jackson Pollock’s Lucifer, and remembering how I felt as a child growing up in the fearful and threatening Cold War United States. I’m including a link a great LA TImes article about the collection and Lucifer. http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cm-anderson-collection-review-20140917-column.html#page=1

This morning, reading the introductory essay in my museum catalog, I got all weepy and teary-eyed over the description of the Anderson Family, and the enrichment they’ve experienced accumulating, enjoying, and endowing their collection. I still can’t answer my friend’s original question about my so-called pilgrimages, but (to quote Greg Kinnear in You’ve Got Mail), There is something…